Case report: keratosis palmoplantaris associated to periodontal disease (papillon-lefévre syndrome)

- Carlos Eduardo Xavier dos Santos Ribeiro da Silva

- Artur Cerri

- Francisco Octávio Teixeira Pacca

- Ricardo Jahn

- Department of ENT/Head and Neck Surgery, UNIFESP, Sao Paulo, Brazil

- Department of Oral Medicine, UNISA, Santo Amaro University, Sao Paulo, Brazil

- Department of Oral Medicine, Santo Amaro University, UNISA, Sao Paulo, Brazil

- Department of Oral Medicine, Santo Amaro University, UNISA, Sao Paulo, Brazil

- Department of Periodontology, Santo Amaro University, UNISA, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Send all correspondence to Dr. Carlos Eduardo X. S. Ribeiro da Silva, Rua Pelotas, 358 – Vila Mariana, 04012-001, Sao Paulo,SP, Brazil Voice /Fax : 55 11 5571-1736

Email adress: dreduardosilva@terra.com.br

Case Report: Keratosis palmoplantaris associated to periodontal disease (Papillon-Lefévre Syndrome)

Abstract

This report describes a rare case of a 16 years old girl with keratosis palmoplantaris associated to periodontopathy or Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. The patient went to Santo Amaro University – Dental College for dental treatment. This report presents the medical and stomatological progression, and suggest how to treat this condition. This syndrome requires a multidisciplinary team for treatment and control and the prognosis is still poor.

Keywords

Papillon-Lefèvre Disease – Hyperkeratosis palmoplantaris – periodontal disease

Introduction and literature review

The Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome or keratosis palmoplantaris associated to periodontopathy was first described by Papillon-Lefèvre, in 1924. It is an autosomal recessive genetic disease, with alteration in the gene CTSC, located in chromosome 11q14.1-q14.4, more precisely in the protein called cathepsin C (Hart et al., 2000; Shafer et al., 1987; Neville et al., 2001; Tommasi, 2002; Allende & Moreno, 2003; Hewitt et al., 2004; Selvaraju et al., 2003 )

It affects children and young adults of both sexes with no distinction. It is a very rare disease, with a prevalence of one in one million individuals. Its main oral clinical characteristics include periodontopathies, premature loss of deciduous teeth, at the age of 4-5 years and of the permanent teeth at approximately 14 years (Allegra & Gennari, 2000; Regezi & Sciubba, 2000; Tommasi, 2002; Siragusa et al., 2000). According to Shafer et al. (1987), only the permanent dentition is affected in some cases.

Patients also present halitosis, intense destruction of alveolar bone, and, in some cases, calcification of cortical bone, pathological tooth mobility and migration, reddish gingiva, with deep periodontal pockets (Tommasi, 2002; Fermin & Carranza, 1986; Allegra & Gennari, 2000; Neville et al., 2001).

Other signs of this syndrome are fragile nails, hypotrichosis, thin and scarce hair, generalized hypohydrosis, hyperkeratosis palmoplantaris, skin scaling, dry skin with a “dirty” appearance, painful deep fissures that worsen during winter, frontal bossing and occasional intracranial calcifications (Fermin & Carranza, 1986; Neville et al., 2001; Shafer et al., 1987; Tommasi, 2002).

Some authors also reported other findings, such as microphtalmus, intracranial calcification, arachnodactyly, osteoporosis, abnormal hepatic function, renal abnormalities and mental retardation (Shafer et al., 1987; Mahajan et al., 2003)

In some countries of the world the diagnosis is practically based on clinical aspects because there are no genetic tests available to confirm the presumptive diagnosis.

The most important oral manifestation is reabsorption of alveolar bone with consequent tooth loss, with no calculus and/or periodontal inflammatory processes to justify this. The possible immunological alterations involved are impaired chemotaxis of neutrophils and, possibly an induced immunological defect caused by an interaction of periodontal pathogens and pocket epithelium (Regezi & Sciuba, 2000; Neville et al., 2001; Ghaffer et al.,1999).

Microscopically, there are alterations characterized by marked chronic inflammation of the lateral wall of the pocket, with intense osteoclastic activity and apparent absence of osteoblastic activity (Fermin & Carranza,1986). Bacterial studies of plaque in a case of Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome showed a flora similar to that of periodontitis and not of periodontosis, and was composed basically of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia and Actinomyces actinomycetemcomitans (Fermin & Carranza 1986; Neville et al., 2001; Robertson, 2001).

Treatment is based on preventive and therapeutical periodontal procedures comprising intense oral hygiene, followed by appropriate orientation, periodontal treatment and referral to dermatologists to treat skin lesions (Tommasi, 2002; Allegra & Gennari, 2000;). According to Tommasi, 2002 and Shafer et al., 1987, it is clear that adequate nutrition and elimination of any eventual systemic factor are essential for disease prognosis. (Mahajan et al., 2993 )

Dental splinting may contribute to longer maintenance. Regezi & Sciubba, 2000, explained that submersion of healthy roots, could stabilize height and alveolar bone conformation and improve prognosis. Other authors presented different protocols, such as extraction of deciduous teeth, followed by antibiotic therapy during and after permanent tooth eruption. Another management would include continuous and combined use of mechanic control of plaque and systemic therapy (specific antibiotic), which could change the course of disease (Neville et al., 2001; Pratchyapruit & Kullavanjaya, 2002).

However, all authors mentioned that treatment is problematic, there are many failures and dental prognosis is very poor (Allegra & Gennari, 2000; Neville et al., 2001; Shafer et al., 1987; ).

Case report

The authors report the case of a 16 years old black girl, came to Santo Amaro University – Oral Medicine Service complaining of “tooth softening”, and no report of pain at all.

The patient reported good general conditions and no use of systemic medicines, and her mother confirmed this status. On regional extra-oral clinical examination, a prominent frontal bossing was observed, as well as scarce and thin hair in the frontal region. Her face was symmetrical with dolichocephalic shape.

On intra-oral examination, teeth presented large root exposures, moderate to intense mobility, migration but there was no salivary calculus or intense gingival inflammation that could justify such bone losses and mobility (Figure 1). Investigating the family history, including a younger brother, nothing important was reported.

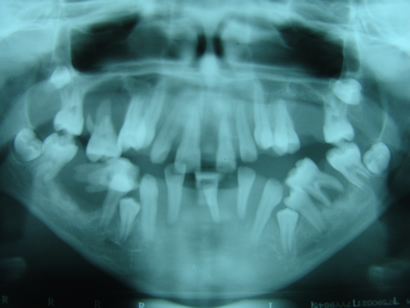

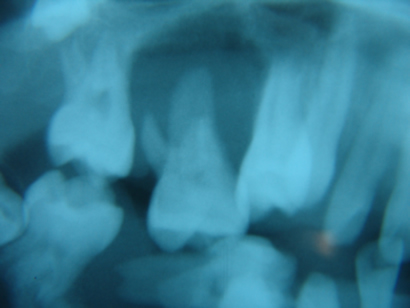

The panoramic and periapical radiographic examinations enabled visualizing great vertical and horizontal bone reabsorption in the maxilla and mandible, predominantly in the molar region (Figures 2 and 3). Other complementary tests were ordered including alkaline phosphatase, complete blood count, glycemia, calcium, phosphorus, skull X-ray (posteroanterior and lateral), femur X-ray, GOT, GPT, urea and creatinine, looking for signs of bone, inflammatory, fibrous or hormone diseases. All results were within normal standards for age and sex of patient.

Therefore, we decided to perform an incisional biopsy of gingival attachment, in the region of the lower left molars and lower incisors. The pathologist report was unspecific chronic recurrent inflammatory process. Therefore, no etiologic or neoplastic agent was demonstrated. The histological analysis was inconclusive but helped ruling out many common diseases in the oral cavity.

On the general physical examination, the patient presented frontal bossing, hypotrichosis, dry skin with fissures and hyperkeratosis palmoplantaris (Figure 4). Based on clinical and laboratory characteristics made a presumptive diagnosis of Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome.

The oral treatment proposed was scaling and root and crown planing of both dental arches, splint fixation of some teeth, encouragement for and orientation about oral hygiene, and referral to a dermatologist to evaluate skin abnormalities. There was a significant improvement in tooth mobility and gingival inflammation. The patient has been constantly followed-up considering the poor oral health prognosis in this syndrome.

Discussion

The diagnosis of Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome was made primarily based on the clinical aspects of the patient, that is, major alveolar bone destruction with fast progression and little dental calculus, besides skin involvement and analysis of laboratory tests. The molecular test specific for Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome is not available in Brazil.

The differential diagnosis of Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome includes other bone diseases and, particularly, hypophosphatemia. This is based on reports by Tommasi (2002), who stated both conditions are carried by a dominant autosomal gene, and their differentiation would lay in the fact that hypophosphatemia presents more severe general and skeletal manifestations. Fermin & Carranza, in 1986, reported that Meleda disease differs from Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome for presenting hyperkeratosis of fingers and palms and no periodontitis (Ullbro et al, 2003).

Management consists of strict scaling and root and crown planing of all dental elements, encouraging and orienting patients to perform an adequate oral hygiene, as well as splinting of affected teeth to provide better oral health conditions. Systemic treatment should be prescribed by physicians.

Conclusions

Participation of a multidisciplinary team is crucial for treating and following-up patients affected with Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. Dentists play an important role in diagnosis considering it is a disease with severe oral manifestations;

When making diagnosis, the clinical examination should be detailed, ordered and complete. A meticulous clinical examination is the basis for a reliable diagnosis;

Diagnosis of oral diseases very often depends on knowledge and choice of relevant laboratory tests that may confirm or rule out diseases with similar clinical picture and progression.

References

Allegra, F; Gennari, P.U. As doenças da mucosa bucal. 1a ed. Santos livraria editora: São Paulo, 2000.

Allende LM; Moreno A; de Unamuno P A genetic study of cathepsin C gene in two families with Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. Mol Genet Metab; 79(2):146-8, 2003 Jun.

Fermin, A; Carranza, JR; Dr. Odont. Periodontia clínica de Glickman. 5a ed. Editora Guanabara S.A.: Rio de Janeiro, 1986.

Ghaffer KA; Zahran FM; Fahmy HM; Brown RS. Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome: neutrophil function in 15 cases from 4 families in Egypt. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod; 88(3):320-5, 1999 Sep.

Hart PS; Zhang Y; Firatli E; Uygur C; Lotfazar M; Michalec MD; Marks JJ; Lu X; Coates BJ; Seow WK; Marshall R; Williams D; Reed JB; Wright JT; Hart TC Identification of cathenpsin C mutations in ethnically diverse Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome patients. J Med Genet; 37(12):927-32, 2000 Dec.

Hewitt C; McCormick D; Linden G; Turk D; Stern I; Wallace I; Southern L; Zhang L; Howard R; Bullon P; Wong M; Widmer R; Gaffar KA; Awawdeh L; Briggs J; Yaghmai R; Jabs EW; Hoeger P; Bleck O; Rüdiger SG; Petersilka G; Battino M; Brett P; Hattab F; Al-Hamed M; Sloan P; Toomes C; Dixon M; James J; Read AP; Thakker N The role of cathepsin C in Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, prepubertal periodontitis, and aggressive periodontitis. Hum Mutat; 23(3):222-8, 2004 Mar.

Mahajan VK; Thakur NS; Sharma NL Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. Indian Pediatr; 40(12):1197-200, 2003 Dec

Neville, B.W; Damm, D.D; White, D.K. Atlas colorido de patologia oral clínica. 2nd ed. Guanabara Koogan S.A.: Rio de Janeiro, 2001.

Pratchyapruit WO; Kullavanijaya P. Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome: a case report. J Dermatol; 29(6):329-35, 2002 Jun.

Regezi, JA, Sciubba, JJ. Patologia Bucal. Correlações Clinicopatológicas. 3a. Ed. Guanabara Koogan Rio de Janeiro, 2002

Robertson KT A microbiological study of Papallon-Lefèvre syndrome in two patients. J Clin Pathol; 54(5):371-6, 2001 May.

- Tooth migration

- Panoramic X-ray with extensive bone reabsorption

- Periapical X-ray – “floating tooth”

- Hyperqueratosis